Come on and spread a sense of urgency

And pull us through

And it's time we saw a miracle

Come on it's time for something biblical

To pull us through

Proclaim eternal victory

Come on and change the course of history

And pull us through

And this is the end of the world -- Apocalypse Please, Muse

Let's meet three of the surviving victims of George W. Bush's judgment. I have very little commentary; their stories speak for themselves.

Faoa Apineru:

Faoa Apineru should be dead.

In May 2005, he was in a humvee driving down a road in Iraq near the Syrian border when a roadside bomb went off right next to him. The blast was enormous. A shard of metal pierced his face and rattled around his brainpan. He was flown to a hospital in Fallujah, then to another one in Germany and to Bethesda, Md. After many surgeries to fix his brain and face, Apineru made his way to the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System hospital for treatment and rehabilitation.

He couldn't move. He couldn't speak. He was barely alive.

....

He's not fully recovered from his wounds. He suffers from severe post-traumatic stress disorder, which is compounded by his brain injury. He still goes to therapy and he talks with counselors at the PTSD center regularly. Not long ago, he had an episode; he saw someone on the side of the road. Looked like an insurgent, like the one who tried to kill him with a horrible bomb, and he had bad thoughts. Thoughts that required another trip to the PTSD center.

"They're the only ones who really know what's going on with me," he said.

....

AP grew up in Samoa. That's about all he remembers from his childhood. The explosion took away most of his memories.

Picture it: You are an adult in your 20s and you have no recollection of where you grew up, who were your best friends, or your first kiss.

AP's mother told him he had gotten into a lot of trouble when he was growing up. His father thought the Marines would be a good place for him to learn discipline and stay out of trouble. He found out later that his grandfather had served in the Marines in World War II.

AP joined the corps in 1996 and worked his way up to communications chief for his unit.

He was in Iraq only once. At least, he thinks so. He doesn't remember any other tours. He has trouble remembering how to spell his name.

Everyone has his or her demons in rehab. For AP, it's the nightmares.

"After the injury, I always think there's people against me," he said. "I know it's not true; I know I'm in the U.S. But that feeling will get me off guard whenever I have pain, or especially when I go to sleep because I have nightmares. My nightmares are so real, I can feel it, I can smell it."

He dreams about getting hit. The dream is always the same. The only variation is when it starts and when it ends.

....

AP went in and out of consciousness. He remembers someone trying to cut off his bloody uniform, and saying that he didn't appear to be hurt.

He thought he was shaken but physically fine. He took off his protective glasses and looked in what was left of the humvee's side mirror. Blood sprayed from his nose and a big gash close to his ear.

"I just thought, 'Oh my God. I'm f -- ed,' " he said.

He thought maybe the gash was just a deep scratch. He tried to stem the flow of blood with his finger. His finger sunk in deep.

....

When he finally came to, he had no idea where he was. He was alone in a room. His hands were tied down.

A nurse came in and saw he was conscious. She called others into his room and when someone talked to him, he recognized an American accent. He spotted a man wearing the chevrons of a Marine gunnery sergeant. Finally, something he recognized. He relaxed. He didn't know it at the time, but he was at the Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Md.

His mother and sister were there, too.

"Who the hell are those people?" he asked a medic.

"Dude, that's your mom," the man replied.

"What's a mom?" AP asked.

He was sent to Palo Alto for rehabilitation in June 2005. He had to learn how to walk and talk and remember again.

It was a long and difficult road. AP hated the hospital. He hated the smell. He sprayed cologne everywhere to get the stink of antiseptic out of his nostrils. He took test after test, and was frustrated that he could no longer think the way he used to think and remember the simplest things.

He stayed up late at night, going over and over the tests until the nurses forced him to stop, to try to sleep. He was moved to a different hospital, but he kept running away. There's a reason for that, one he's reluctant to share because people think he's nuts.

"I'm seeing people, you know, who are dead already," he said. Not guys he knew. People he never met before.

Angel Gomez:

Angel Gomez just wants to drive.

That's what he was doing when he got hit in March 2005: driving a 7-ton truck in the city of Ramadi. A piece of shrapnel hit his head just behind the ear. It took off a big chunk of skull.

When he got to Palo Alto, he was barely alive. Couldn't walk. Could barely talk. His family wondered if he would ever recover.

Gomez has had surgery to replace a portion of his skull. For a long time, he wore a bicycle helmet to protect his unprotected brain. Now, his head is intact and the only sign of his injury is a long, ragged scar that goes up over his crown and back down toward his neck, a little like a ram's horn. His hair is growing longer and covers most of the scar. He wears a cap most of the time.

But the brain injury has caused physical problems. He can move his right shoulder, but his hand doesn't work. He can walk now, but he needs a brace on his right leg. He's not sure if he'll ever regain full movement on his right side.

Gomez has a sweet smile and bright eyes. He speaks haltingly, and peppers his sentences with "you know," "like" and "whatever." He will be in the middle of a sentence and stop because the right word, an easy word, simply vanishes from his vocabulary without warning.

....

Does he remember it?

"Oh yeah, I remember it," he said.

Gomez was behind the wheel when the blast hit. The explosion rocked the truck, but didn't knock it over. A jagged shard of metal flew through the air and hit him in the head. He was otherwise unhurt.

"I was really dazed, you know," he said. "I was like, 'Whoa, what happened?' "

His good friend, Jesse Aguilar, ran to the vehicle to check him out.

"I saw his face," Gomez said. "He was shocked or whatever. I guess he thought I was gonna die.

"My brain was like showing and stuff. I didn't know."

Gomez said his skull looked like an egg does when it's dropped on the floor. He had pieces of skull in his brain.

Gomez stayed awake as the corpsmen and Marines put him in a humvee and drove to an aid station. He said a medic had to prevent him from touching his head, so he wouldn't hurt himself any further.

....

A couple of weeks ago, Gomez was discharged from the hospital. He moved into an apartment nearby so he could take a bus to the hospital for therapy. But he was itching to drive. He just wanted to get into his truck and hold the wheel in his hands. And move.

Shortly after he moved into his new apartment, he was on the bus, talking to his girlfriend on his cell phone, and he had a seizure. He lay on the floor of the bus, jerking uncontrollably, as his brain fought with itself.

His dreams of driving again went out the window that day. The doctors say he'll need another six months before he can even think about getting behind the wheel of a vehicle again.

Tim Jeffers:

At 22, Tim Jeffers is learning to walk.

He's missing both legs just above the knee. He has high-tech prosthetic legs with feet encased in new black-suede tennis shoes.

Rehabilitation for him -- getting out of the hospital and on his own -- will take some time.

He lost both his legs just above the knee. He lost a finger, his right eye and a chunk of skull just above his right temple. The wound healed but swelling remains, causing his head to be misshapen. He often wears a bicycle helmet to protect his brain.

....

Jeffers recently had surgery to implant a synthetic piece of bone into his skull. A couple of days later, he developed an infection and the piece had to be removed.

It will be another six months before the doctors try that procedure again.

....

Jeffers was a convoy commander in Iraq, and had been in-country about four months when he got hit. It was May 18.

"We were in a convoy, running along," he said. "Over the radio, someone said an IED went off between a military vehicle and civilian contractor vehicle with us. We were at a security halt, to make sure nothing else happened.

"I was at a T-intersection at the halt, so I was looking around. There was some trash in the area, so I was looking to see if there were any loose wires sticking out. I turned around and there were two mufflers in the middle of the road. And then, "Bang." One of them blew up."

Jeffers was about 3 feet from the bomb when it exploded. His legs were mangled and the bomb blew out his eye. It took out a small piece of his skull.

"I was awake the whole time waiting for the helo," he said. "I was yelling and screaming and swearing. That's all I remember. Three or three and half weeks later, I woke up."

He doesn't remember going to a surgical hospital at the American base at Al Asad.

The blast didn't take off his legs, but they were mangled. "As far as I know, I got my first amputation in Al Asad," he said. "I don't know how many amputations total I had. I think there were about four, going higher and higher on the legs.

"The next thing I remember is waking up in the hospital with my dad's face over me. He was telling me to blink once for no and twice for yes, and asking if I could hear him. So I blinked twice. I kinda knew why I was in there, even though it took me a couple of minutes to figure it out."

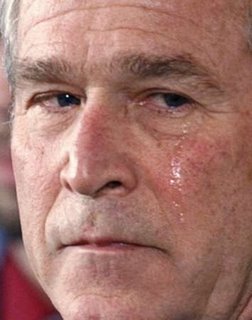

I have no sympathy for Bush's crocodile tears, especially since he keeps insisting on upping the ante, keeps itching to double down, somewhere, anywhere. I hope he cries every day with the knowledge of what he's done, and what he still wants to do. I hope he prays in desperation to whatever spiteful, retributive deity he thinks he believes in for some mask of solace. I hope it gives him nightmares, night after grueling night. The entire world has literally made every effort to try to talk him out of his tree, to steer him away from the path of futility, stupidity, insanity. He has had his chance -- many chances -- to make things right.

He has no right to cry, to grieve. He got exactly what he wanted.

These people, and hundreds of thousands more like them, have to live with the consequences of Bush's decisions every day for the rest of their lives. Why shouldn't he?

No comments:

Post a Comment